Een alternatieve geschiedenis van West-Europa (Anthony Pagden, The Enlightenment and why it still matters) doet een gedachtenoefening: Wat als Reformatie, Renaissance en Verlichting niet zouden hebben doorgezet… [een tamelijk gloomy verhaal]. En dan een parallelverhaal over hoe de Verlichting in de Arabische wereld wel degelijk is gefnuikt, zo ca. 1150

Inhoudsopgave

What if, to begin with, the Protestant Reformation had never taken place?

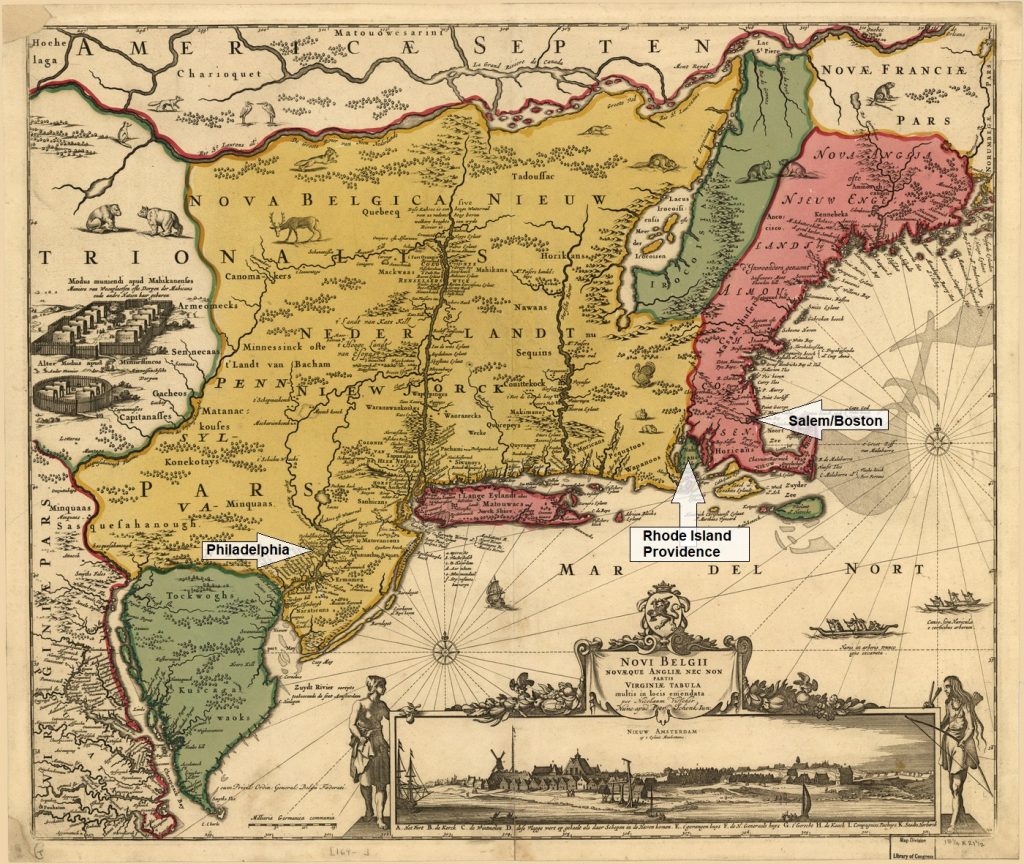

Luther, who was burned as a heretic in 1521, has gone down in history as nothing more than yet another troublesome friar hankering after the purity of the early Church. Christianity, although rarely ever at peace, remains united. The discovery of America has led to some flutters of uncertainty within the universities, but any thought that it might present a challenge to the traditional view of the laws of nature or God have been successfully repressed. There have been no French Wars of Religion, no English Civil Wars. The Revolt of the Netherlands, lacking ideological cohesion and foreign aid, has been swiftly suppressed. There has been no Thirty Years’ War. Spain continues to be the richest, most powerful nation in Europe and remains locked in an unending struggle with France. Copernicus and Galileo, Bacon, Descartes, and Mersenne succeed in creating a new kind of Renaissance, which flourishes for a while under moderately tolerant regimes. Thomas Hobbes, however, although he enjoys some small success as a mathematician, eventually follows his father into the Church and dies, like him, an embittered alcoholic. John Locke is an obscure doctor at Christ Church, Oxford, renowned only for the silver tap he succeeded in inserting into the Earl of Shaftesbury’s lower intestine without killing him in the process. Newton achieves recognition as a gifted astrologer and competent administrator and some notoriety as a somewhat heterodox theologian.

By the end of the century the “Scientific Renaissance,” as it later came to be called, has been silenced, the heliocentric theory and Descartes’s atomism between them having proved too much for the Church to tolerate. The next generation has nothing to build on. .. Western Christendom drops behind its centuries-old antagonist to the east, the Ottoman Empire. In 1683 Vienna falls to the armies of Sultan Mehmed IV. Russia, or “Muscovy,” as it still calls itself, backward and divided, is easily defeated and overrun in January 1699. Spain and France still control the western Mediterranean and dominate most of northern Europe. But threatened by the seemingly irresistible Ottoman armies, they become increasingly theocratic and resistant to any innovation, from mechanical clocks to vaccination, which, they fear, might offend their ever-unpredictable God. The Encyclopédie is nothing more than an uninspiring French translation of Chambers’s Cyclopaedia. Diderot manages a certain literary fame but dies in prison in the Château de Vincennes in 1749. Rousseau lives, and dies, a penny-grubbing musical critic. His novel Julie, or the New Héloïse enjoys moderate underground success but is then burned in Paris by the public executioner. David Hume, after an early attempt to revolutionize philosophy that is swiftly silenced by the “zealots,” lives as the librarian at St. Aloysius’ College in Glasgow and writes a popular history of the kings of England. Voltaire achieves both fame and popularity as a playwright and poet but is finally forced to seek refuge in Switzerland, which has preserved a degree of independence and a reputation for toleration, where, to his horror, he is soon joined by Rousseau. Bougainville never leaves France, and Banks eventually becomes a dyspeptic Lincolnshire squire with a passion for horticulture. Vico is elected to a chair in theology at the University of Naples, and Kant lectures on a variety of topics to listless students in Königsberg, renowned only for his short essay “On the Beautiful and the Sublime.”

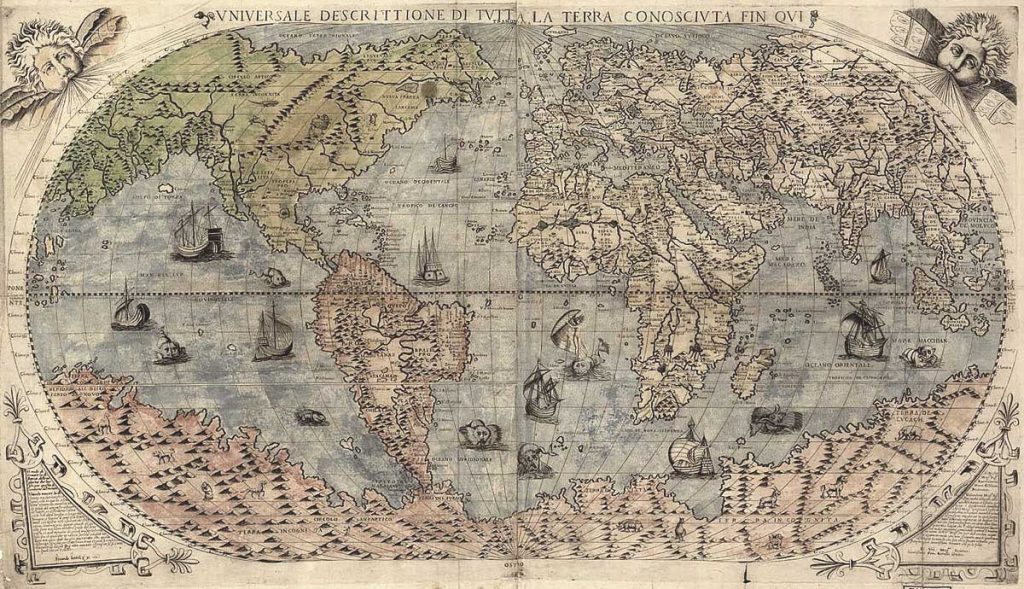

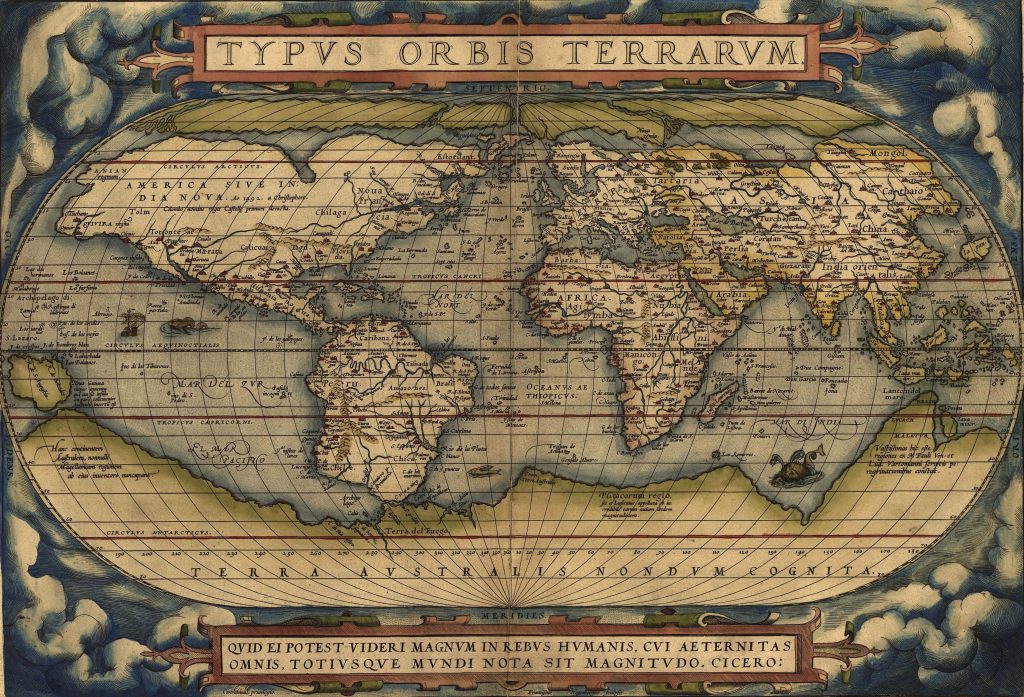

Lacking any capacity for scientific or social innovation, the European powers not already under Ottoman control steadily decline until finally, in May 1789, Sultan Selim III marches into Paris. Within a few years what the English ecclesiastical historian Edward Gibbon had predicted in 1776 has come true, and “the interpretation of the Koran is now taught in the schools of Oxford and her pupils demonstrate to a circumcised people the sanctity and truth of the Revelation of Mahomet.”1 United in one massive religious and political community, which reaches from the Himalayas to the coasts of Scotland, the Ottoman Empire survives into the twentieth century. In size it has outstripped ancient Rome, but, as in ancient Rome, the only changes that have occurred within its frontiers in nearly half a millennium have been literary and architectural. In all other respects, like Rome, it firmly imagines itself to be the final end of history and has therefore no need to examine the ideals and assumptions on which it is based.2 Ever obedient to God, his Prophet, and his laws, it continues on its unbroken course. Having long since given up any aspiration to influence the future course of events, everyone waits for something to arrive from outside. As for the Romans—or perhaps they are Byzantines, as in Constantine Cafavy’s allusive poem “Waiting for the Barbarians”—for these imaginary Europeans only a crude barbarous people from beyond the borders of the empire can offer “a kind of solution.” But the barbarians never come and may, in fact, no longer exist at all.

An utterly implausible flight of fancy? An illusion?

Perhaps, but something not wholly dissimilar did, in fact, befall the [sta_anchor id=”islam”]Islamic world[/sta_anchor]. During the reigns of the Caliphs al-Mansûr (712–75) and his successors Hârûn-al Rashîd (786–809) and al-Ma’mûn (813–33), an entire school of Hellenizing philosophers, jurists, and doctors grew up: men like the surgeon Abul Qasim Al-Zahravi, known as “Albucasis”; the mathematician and astronomer Muhammad ibn Mûsâ al-Khwârizmî, after whom a crater on the far side of the moon is now named; Abû or Ibn Sînâ, called “Avicenna” in the West, the author of a vast treatise that brought together all the medical knowledge of the ancient Greek world then available, from Aristotle, Hippocrates, and Galen; Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni, physician, astronomer, mathematician, physicist, chemist, geographer, and historian, who in 1018 made calculations, using instruments he had created himself, of the radius and circumference of the Earth that vary by as little as 15 and 200 kilometers from today’s estimates. The best known in the West, however, was Abû al-Walîd Muhammad ibn Rushd, or “Averroës” as he was called by his Latin readers, who was so highly regarded in the Christian world that he became known simply as “The Commentator” (just as Aristotle was known as “The Philosopher”)—which is how he appears, peering over the shoulder of Aristotle, in Raphael’s great fresco The School of Athens in the Sistine Chapel. But Averroës was not only the greatest of the Arab Muslim scholars and perhaps the most influential of all Muslim philosophers, he was also the last. In the late twelfth century the Muslim clergy began a concerted onslaught on translation from the Greek and against all forms of learning that did not derive from either the Qur’an itself or from the sayings of the Prophet. When Averroës died in 1198, in exile in Morocco, a victim of this war against “philosophy” and its adherents throughout the Islamic world, the “Arab Renaissance” died with him. Islamic power, Sunni and Shia, under Mongol, Turcoman, Safavid, and Sassanid rulers remained dominant within western and central Asia for another four hundred years, during much of which time the Ottomans gobbled up large tracts of eastern Europe. But inside the Muslim world there was little of importance that separated the twelfth century from the seventeenth. Certain of its own superiority, Islam ultimately repulsed any attempt to bring about any kind of change, in particular if it arrived, or seemed to have arrived, from the West.

In this case, however, the barbarians did arrive, first in the shape of the Austrians, then the Russians, who inflicted a humiliating peace treaty on the Ottomans at Karlowitz in the Voivodina on January 26, 1699, and then the French. The European powers nibbled unceasingly away at the frontiers of the Ottoman Empire, until finally, in the early nineteenth century, the sultans, desperate to preserve what still remained to them, began slowly to adopt western technologies, western education, western laws, and, in 1876, to the dismay of the clergy, a European-style constitution and even a parliament, if only a somewhat toothless one. In 1919, having chosen the wrong side in the First World War, the Ottoman Empire, with the exception of Turkey itself, was dismantled and parceled out among the victorious allies.

[sta_anchor id=”europe” unsan=”Europe” /]Without the Enlightenment, Europe’s history could well have followed a similar trajectory. For it is not only the science of human understanding itself that we owe to the Enlightenment; it is, as I have argued, also the ways in which we all, in the West, live our political and social lives. “Citizenship,” the concept that undergirds all modern western political creeds, has its origins in Greece and Rome, but the modern understanding of the word, and all that it implies, is a creation of the Enlightenment. Modern liberal democracy—the kind of political system that, for better and sometimes for worse, governs most modern societies—is a creation of the Enlightenment, refined and institutionalized during the course of the nineteenth century. And although the idea of a law of nations is an ancient one, the modern understanding of what that might mean in a world of ever-expanding nation-states we owe to the Enlightenment. It was, after all, one of its last, if often most idiosyncratic, representatives, Jeremy Bentham, who coined the term “international law.”

Voetnoten

- Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, LII, 16. Gibbon’s predication, however, was about what might have become of Europe if an invading Arab army under the command of ‘Abd Rahman, the governor of Al-Andalus, had not been defeated at Poitiers in southern France in October 732.

- On the reasons for Rome’s failure to progress beyond the intellectual state it had arrived at in the first century, see Aldo Schiavone, The End of the Past: Ancient Rome and the Modern West, trans. Margaret J. Schneider (Cambridge, Mass., and London: Harvard University Press, 2000).

‘Onze Lieve Heer op zolder’ is de negentiende eeuwse naam van de schuilkerk die de rooms-katholieken in de zeventiende eeuw inrichtten op de zolder van een groot (gecombineerde) herenhuis aan de Amsterdamse Oudezijds Voorburgwal. Van binnen een kerk, van buiten niets bijzonders te zien.

‘Onze Lieve Heer op zolder’ is de negentiende eeuwse naam van de schuilkerk die de rooms-katholieken in de zeventiende eeuw inrichtten op de zolder van een groot (gecombineerde) herenhuis aan de Amsterdamse Oudezijds Voorburgwal. Van binnen een kerk, van buiten niets bijzonders te zien.

Peter Berger (1929-2017) was een invloedrijk godsdienstsocioloog. Zijn boek uit 1967 The Sacred Canopy vestigde zijn naam op dit terrein. In dit boek combineerde hij de secularisatiethese van Weber met zijn eigen visie op religies als ‘sociale constructies’. Al snel zag hij de blikvernauwing. In de jaren 1990 stelde hij dat Moderniteit leidt tot pluraliteit (als feit) op religieus terrein en dus tot de vaststelling dat men niet meer op dezelfde manier religieus kan zijn als vroeger, nl. vanzelfsprekend. Dit kan vervolgens zowel tot relativitering als tot fundamentalisering van het religieuze leiden. Secularisatie is dan een optie (Europa), maar geen dwingend gevolg.

Peter Berger (1929-2017) was een invloedrijk godsdienstsocioloog. Zijn boek uit 1967 The Sacred Canopy vestigde zijn naam op dit terrein. In dit boek combineerde hij de secularisatiethese van Weber met zijn eigen visie op religies als ‘sociale constructies’. Al snel zag hij de blikvernauwing. In de jaren 1990 stelde hij dat Moderniteit leidt tot pluraliteit (als feit) op religieus terrein en dus tot de vaststelling dat men niet meer op dezelfde manier religieus kan zijn als vroeger, nl. vanzelfsprekend. Dit kan vervolgens zowel tot relativitering als tot fundamentalisering van het religieuze leiden. Secularisatie is dan een optie (Europa), maar geen dwingend gevolg.

Olivier Roy (

Olivier Roy (

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961).

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961).